The Unlikely Doctor by Timoti Te Moke Extract

- Allen & Unwin NZ

- Jul 23, 2025

- 12 min read

Read an extract from The Unlikely Doctor by Timoti Te Moke.

Chapter 7

A New Beginning

There are things I won’t say about what it was like to be in a gang. There are thousands of stories about that life. I feel like that story is not my story to tell. However, there are things that happened to me, experiences I went through, that give an insight into me and how I’ve ended up where I have. They’ll also help me explain why I think gangs have a place in this country and why the usual policies to tear them down will never work.

I’ll give you an example of something that will demonstrate why I think that. It’s an incident that happened one of the times I was in Mt Eden on remand; an incident that illustrates my singleminded focus, and the attitude within gangs that you never, ever back down. I was eighteen years old, waiting all night in the dark of my cell, preparing to fight and prepared to die. I’d torn the legs off my bed to use as a club, ripped up the mattress from my bed and wrapped it around my body to soften any blows, had a toothbrush sharpened up as a rudimentary but hopefully effective weapon in my hand, as well as a shoe ready to shove under the door to slow the progress of the likely invaders. I was ready; as ready as I’d ever been. If I die, some of you fuckers are coming with me, I thought to myself.

The build-up to this night had started a few days before. I’d been sitting at a bench in a concrete cubicle in the east wing. This was when the remodelling of the prison had happened. Under-twenties, both remand and sentenced, were now in the east wing with the sentenced on the bottom landing and the remand on the top landing. The day yards were separate. I was playing the card game Euchre with some guys when I heard noises behind me — heavy footfalls, dum, dum, dum, dum. I turned around and saw five guys from another gang had jumped over a wall — and I didn’t have to be a rocket scientist to know they were there for me. Four of the guys were from one gang. And with them was another guy — he had been on the bus I’d thrown the petrol bomb at. They all started taunting me to come and fight. I looked across at the guys I was playing cards with and said, ‘I’ll catch you later.’ As I walked out into the yard, I thought: Yeah, this is gonna hurt.

They were indeed there to deal with me. And they did; I got a hell of a beating. By the time the screws arrived to pull them off me, plenty of damage had been done so I was taken to the prison infirmary. After I got fixed up and had been given all the painkillers I could get away with asking for, the prison bosses wanted to send me to the protection block. They figured the other gang would want to finish off what they’d started. And they were right to think that.

‘Fuck off, man, I’m not going to protection,’ I told them.

‘But they’ll kill you,’ the screws replied.

‘I’m not going.’ I was willing to die rather than be a fucking coward and go to protection. It wasn’t that I wanted to die; it’s just that I was never ready to back down or avoid what was coming to me. There was no fear.

Side note: if any politician thinks that telling a gang member to ‘take off their patch or else’ will have any impact at all, they are deluded. The only response will be ‘Or else what?’ Push someone like that into a corner, and you can’t expect them to just lie down and take it.

Anyway, off I went, back to the yard. Later, I was sitting in my cell when the guy I’d thrown the petrol bomb at came in to speak to me. I reckon I need to explain that, too: despite what you might think, prison gangs are not constantly engaged in violence. There can be moments of nuance and calm when there are discussions and arrangement. One moment it can be full-on and hyper- violent with everyone brimming with murderous intent, and then the next day the smoke has cleared away and it’s like it never happened. Everyone has to live together, after all.

So there I was with this guy. He’d come to ask me what was happening, why I was there. I told him I was due in court the next day, and I’d probably end up back inside. What this meant was, if I got sentenced back to ‘the Mount’ I would be coming back here but this time I’d be downstairs where the sentenced people were. ‘Here’s the thing,’ he explained to me. ‘We’re cool now, but the guys downstairs? They want to kill you.’

Although he didn’t say it directly, I knew they would be discussing right now whether to come for me before I went to court, or wait for me to return . . . and come to them. This was why I was spending the night sitting in my cell armed up and ready to fight for my life.

Come morning, I heard the guards’ footsteps along the corridor and the jangle of keys as our cell doors were unlocked. Here we go, I thought. Those guys will be charging up the stairs to my cell any minute. And I waited, and I waited . . . but the attackers never came. I guessed they thought it would be easier to wait for me to come back.

Off I headed to face the judge, expecting to be sent back to Mt Eden. But, for one of the few times in my life, it worked out well for me. Somehow the case needed to be remanded. I got bail, and walked out of the court. So I was saved.

+ + +

Saved is the right word for what happened that time. It was the timely — albeit coincidental — intervention of the judge that stopped me getting fucking killed. But mostly, when I somehow escaped dangerous situations in my life, ‘saved’ is not the right word. Being saved implies something passive, something that happened to me. Most of the time, though, I got out of situations because of something inside me that drove me to do so.

Often it was just a will to live — I didn’t want to die. Don’t get me wrong; there were plenty of times when I did have suicidal thoughts, but they never took root. I’d be heading into a spiral, thinking about some of the things that had happened to me, fucked-up thoughts flying through my head; I’d reach for something to get me high, inhale it, and the thoughts would shake loose.

It’s hard to explain this thing inside me that drove me to get out of situations, or to find another way. I don’t know what it was. But there are a couple of times in my life when it was an obvious presence. Here’s an example. I was in Waikeria Prison, in my cell, only eighteen but already well and truly institutionalised. I felt more comfortable in jail than I did outside.

I had a month to go on my lag. My cellmate and I had some weed and we’d sparked it up. I was off my fucking face, absolutely zoned. I looked up towards a thick glass window which was behind steel bars, and I could see the sky. But it looked different. I’d never seen anything so brilliant in all my life. It was stunning and wondrous. That’s all I was thinking about. But then, a thought popped into my head; out of the blue, you could say: Next time I’m back inside, I’m never leaving. It wasn’t a morbid or depressing thought, just a realisation that this was my life: the cops were going to keep hounding me until they got me on something serious, or I ended up killing someone.

And then another thought appeared: It doesn’t have to be that way. There was no big flash of light, no thunderbolts or any ‘Come to Jesus’ thing. Just a realisation. A response — from somewhere — to my previous thought.

I can’t explain why it happened. But it stuck with me. Huh, it really doesn’t have to be this way.

In stories like mine, people are always looking for ‘the moment’. The exact minute when things changed forever. I’m here to tell you: that’s bullshit. It doesn’t work that way. Life isn’t a fairytale. There is no Hollywood script. Choirs of angels don’t suddenly appear. But for sure, when I look back, this was a critical episode, one where something prompted me to reconsider my ways, what was happening with my life. Of course it’s not the case that from that moment on, everything changed in an instant and stayed that way. It’s not like I stubbed out the joint, went clean and lived happily ever after. It’s more like something started smouldering, a slow evolution beginning to unfold. The seeds had been planted, if you like.

At the end of that prison sentence, I went back to Auckland and, from the outside, it looked like nothing much changed. I was still in the gang, I was still getting in drug- induced trouble, still getting arrested. But I was disgruntled with being part of the gang. You know those break-up conversations which go ‘It’s not you, it’s me’? That was how I was feeling. I had nothing against the group. It just wasn’t the life I wanted. I thought, Nah, this isn’t me — even though, when I was in I was 100% in, I was willing to die for them. But I’d always been a loner, and I wanted to go back to that.

So, after about a year of mulling things over, I went to the leaders and said: ‘I’m leaving.’ That’s about the last thing I remember. I got a beating, and it cost me some time in hospital.

You’ll never hear me complain about that, though. Those were the rules. That was what I had signed up to, a price I always knew I would have to pay. There’s no evolution without consequences.

I bear no animosity, and in fact I see some of the bros around from time to time and we’ll have a kōrero. No hard feelings.

+ + +

Reflecting on my time in the gang, I can see how it helped me begin to find my identity, to understand that I wasn’t alone in feeling targeted, and to figure out that the way society saw me was nothing personal — it was the way society and our dysfunctional system saw everyone who was like me.

What do I mean by that? I realised that all this hatred I felt was directed towards me, all the resources put in to locking me up in prison, to taking away my liberty, to make me less than what I was — it was happening to a whole group of us. And who was ‘us’? Let me put it like this: how many well- educated people end up in gangs, end up in prison? How many wealthy people end up in gangs? How many people whose parents own a house end up in gangs? Fuck all, that’s how many. And how many of the people who end up in gangs, end up in prisons, are brown? Is that a coincidence?

Being in the gang gave me a moment in time when I came to terms with where I was from and what I was dealing with, and could see that society was tilted against us; that there were those who sought to manipulate the system and the laws of this country to subjugate us and prevent us from succeeding. I saw the biases within education, within employment, within health, within housing, within justice.

Time and again, the mentality of many politicians is to ‘crack down’ on gangs, to lock up gang members as if just doing that solves the problem. Guess what? It doesn’t. Gangs reflect society and its cancers; they are like a mirror of what’s going on, the downfalls and the problems. You can’t just lock ’em up and look away. That doesn’t fix the conditions that help gangs thrive, it doesn’t mitigate against the prejudices inherent in our country. If you ban patches and lock people up, all you’re doing is throwing a cover over the mirror. It fixes nothing. Oh, and by the way, you think that taking a patch off someone is going to stop them being intimidating? Give me a break. It will push people closer together, strengthen their unity against the oppressor.

Being in the gang gave me a sense of belonging. To a kid who grew up poor, who grew up being abused, who was being arrested all the time and getting smacked around and racially abused by cops, of course it was attractive. Within the gang, I perceived the sense of unity as love and admiration. It wasn’t, but is it any wonder I was confused?

+ + +

Having decided that gang life was not for me and that I wanted something else — needed something else — I had a decision to make. What was it I was looking for? I had no idea.

I started doing odd jobs around Auckland, then got put on a government work scheme: a twelve- week course to help me find a job. Out of that I got some interviews and landed an apprenticeship on a building site. I actually helped build the Westfield mall in Newmarket. If you take down some of the panels on the walls, you’ll find my name written inside.

Initially things went well. I enjoyed the work, and there was a good bunch of guys. But underneath it all I was still a mess, still fucked up by all the things in my head. I hadn’t dealt with any of it. And so I still had that urge to feel numb, to avoid thinking about shit. I’d get together with mates at the weekend and get off my face.

Things deteriorated. A guy turned up on site who I knew — the guy from another gang whose shoulder I’d put my hand on in prison. We were both out of the gangs now and trying to stay on the straight and narrow. But the bad habits started coming back. I wasn’t just boozing during the weekends any more — we were getting off our faces every night. I started not turning up for work, and things went downhill rapidly.

More stupid shit; more stupid convictions; more petty attention from the cops with no sign they’d ever give me a break. My record started stacking up again: disorderly behaviour, littering (I accidentally dropped a whisky bottle) and, would you believe it, ‘insulting language’. Yes, that’s an actual crime, for which I got taken to court and fined $75. Fuck me.

Then the guy I’d started hanging out with got locked up for breaking into a house — it was an early ‘home invasion’, before anyone knew what that was. It was a bit of a wake-up call for me. I couldn’t see things ending well in the situation I was in, on this downhill slide. There was only one future I could see: sooner or later, I was going to end up back in prison for a long, long time. It was time for another restart.

That internal imperative driving me to get out, to find another life, kicked in again. I made a split- second decision: I had some money, so I quit my job and went to Australia with another guy. I was twenty-one. We jumped off the plane in Sydney and I was carrying a small army bag with some jeans, some shorts, underpants and socks and that was about it.

I didn’t have much of an idea about what I was going to do. We headed to a backpackers for the night, then the next day hit the streets looking for work.

I got the odd labouring job, but it was tough being without steady work. And I discovered that being in a different country didn’t mean I’d be any further away from the mess in my head. So I started acting up again, a little of the same shit in a different country. About three weeks after we landed, I went out with the guy I’d come over with and another Kiwi, and we got off our faces. By the end of the night I was out of it and trying to break into a car. At the time, it made total sense — we had no money left, so how else were we going to get home? The police had other ideas, and I got arrested.

I spent a few days in the cells at the Newtown police station. Like I said, same shit, different country. I got bailed to the place we were staying at, a flat with this cool Greek guy. As my court date approached, I thought, Fuck this — let’s get out of here. So we took off to Melbourne. I never did go to court in Sydney.

In Melbourne, we stayed with some friends of my mate’s in this big party house. I’d discovered that Australia was another scene altogether for drugs. You could easily get your hands on anything, so I started experimenting with all sorts. It was wild, and it became a theme of my time in Australia, especially early on.

The guy I’d come across with decided Australia was not for him, so he moved back home. But I stayed on and started settling in a bit, getting plenty of work and earning some good money— re-stumping old houses, putting up fences around industrial sites, furniture removal. I was pocketing about $150 a day, a decent amount in those days, but I was spending almost all of it on drugs. The more I used, the higher my tolerance got.

I moved back up to Sydney and found some removal work with a guy I knew. He was really into his drugs as well, so we worked hard and partied harder. I didn’t really drink, but I was using heavy drugs. Heroin to chill me out and relax me, and lines of cocaine to get me going. It really helped with the furniture moving — which was good because I’d developed a really expensive habit so I needed to be working.

The drug culture in Sydney at the time was crazy. Having drugs was like having a cup of tea. You’d go around to someone’s house, and they wouldn’t put the kettle on — they’d pull out some shit. There were heaps of junkies around, and I’d look at them — never looking down at them, though — and think, I don’t want to end up like that. Life was good, but I was living on an edge I knew I didn’t want to fall over.

You know what happened next, right?

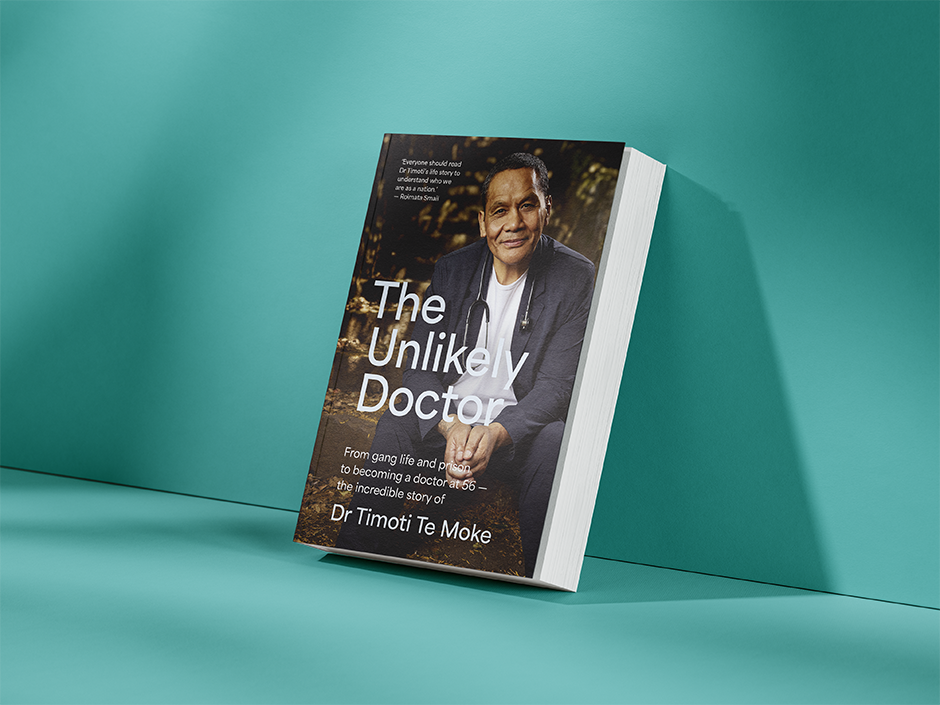

The Unlikely Doctor

by Timoti Te Moke

From gang life and prison to becoming a doctor at 56 - the incredible story of Dr Timoti Te Moke.

Comments