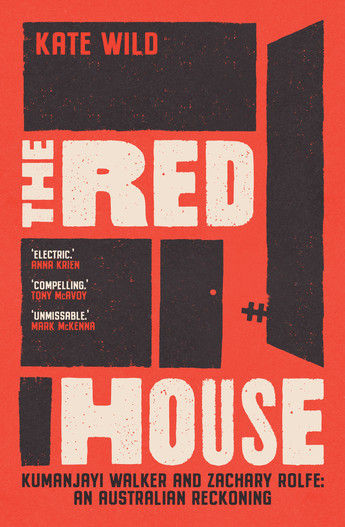

The Red House Extract

- Allen & Unwin

- Aug 26, 2025

- 4 min read

Read an extract from The Red House by Kate Wild.

In 2019, 19-year-old Warlpiri man Kumanjayi Walker lost his life in a police shooting in Yuendumu, Northern Territory. This took place inside what locals called the “red house”.

Constable Zachary Rolfe was charged with murder, the first Northern Territory police officer to face such charges in decades.

In 2022, after a nationally watched trial, Rolfe was acquitted, sparking urgent debate about race, justice and truth-telling in Australia.

In The Red House Walkely Award-winning journalist Kate Wild tells the story about what that single, tragic moment reveals about Australia’s unfinished cycle of violence and how we move towards truth and reconciliation.

Read an extract from The Red House by Kate Wild.

THE GWEAGAL SHIELD

DARWIN, 2020

An Aboriginal man I knew from Darwin described the impact of Kumanjayi’s death as ‘celestial’. It continued beyond the grave.

This man’s family had been in the Territory for hundreds of generations. His father and grandfather had been stolen from their families by white authorities.

‘The NT is the mixture of everywhere else in Australia. It is Australia, but it’s Australia in direct contact with Aboriginal people. We reflect to the nth degree Australian society,’ he told me.

The police shooting of an Aboriginal teenager in Yuendumu connected with his life at every angle. He struggled to find an image to express its enormity. ‘The closest thing I can think of is the bullet hole that goes through the shield, from first contact. It’s that same continuation. Where is this going to go to? What will this manifest into?’

He fretted that the comparison was melodramatic, but he fretted even more about the trouble it would cause if people he lived and worked with knew his private musings, so here I will call him Jim.

The shield Jim was referring to is one of countless Aboriginal artefacts in London’s British Museum. According to the descriptor beside its display case, the Gweagal shield ‘represents the moment of first contact between the British and Aboriginal Australians at Botany Bay in 1770’.

Captain James Cook, who, Australian children learn, ‘discovered’ Australia in 1770, recorded the moment he claimed the shield at Botany Bay (Kamay).

When he and his soldiers landed on the beach, one Gweagal man threw a rock at them, and another threw a spear, Cook wrote in his diary. He fired in retaliation and the man he hit picked up a shield to defend himself. According to Aboriginal historians, the local who picked up the shield was Cooman. Gweagal stories said two spears were launched at Cook’s party, Cooman dropped the shield when he was shot and Cook claimed it as a souvenir.

Two hundred and thirty-two years later, Jim’s awareness of the impact of a young Aboriginal man being shot by the police came from calls he received after Kumanjayi’s death. He was used to hearing from the families of children in contact with the legal system, but in these calls there was ‘an immediate fear of being killed by police’.

‘Before, it was that my son’s in police custody and he’ll go to jail. Now, it was if he’s in police custody he’ll be killed,’ Jim said. ‘It’s not just a demonising, it’s a loss of humanity— that towards Aboriginal people you don’t have to be human, you don’t have to be humane.

And then that leads to this violence. ‘It sort of feels like people are out at war with Aboriginal people.’

I thought of the kids on the streets of Alice Springs at night and the people who wanted the army to ‘sort them out’. The war footing both sides took did feel melodramatic, I admitted.

Not if you were living it, Jim replied.

People were confronted by Indigenous disadvantage. ‘You see Aboriginal people every day, their poverty, their issues, you can’t avoid it. The only way you can avoid it is to switch off inside,’ he said.

I had known Jim for years but we had never spoken like this. Kumanjayi’s death had left him raw.

There was a power vacuum in Aboriginal communities, he said. Cultural authority and autonomy in the Northern Territory had been destroyed by the Intervention— a suite of policies brought in by the federal government in 2007 and carried on in different guises by every government since. That vacuum was being filled by Aboriginal anger; Jim was seeing it more and more. Anger at not being listened to; anger at being ignored, oppressed.

He saw it in courtrooms when people declared they did not recognise the court’s authority, ‘because I’m a sovereign person’. It had been happening well before Covid conspiracies bolstered the sovereign citizen movement. This was about Aboriginal people trying to claim their lives back from the government.

‘Try and understand why it’s happening,’ Jim told the white lawyers he spoke to outside court. ‘That person is crying out— “I want you to respect me” as an individual in a racist, failing system. But I want you to respect my culture.’

The call was generations old, he said.

‘That older generation are still calling out— the constant message has always been respect.’

Extracted from The Red House by Kate Wild.

Published by Allen & Unwin.

The Red House

by Kate Wild

How the fatal shooting of Kumanjayi Walker exposes the power of race in Australia, from Walkley Award-winning journalist Kate Wild.

Comments